The Diseases

Myositis is a rare disease and is a general term for inflammation of the muscles, or inflammatory myopathy. Myositis includes the following diseases: dermatomyositis, polymyositis, inclusion body myositis, juvenile myositis and toxic myositis, the latter having been caused as a side effect from certain medications, the most common being statins In all cases, they cause inflammation within muscle and muscle damage. Many of these conditions are considered likely to be caused by autoimmune diseases, although autoimmune conditions can be activated or exacerbated by infections or viruses.

Polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and juvenile myositis are all autoimmune diseases, meaning the body’s immune system is attacking the muscle. While the immune system may also cause muscle damage in inclusion body myositis, this may not be cause of this disease. Although myositis is often treatable, these diseases are poorly understood and do not always completely respond to current medications.

General symptoms of chronic inflammatory myopathy include slow but progressive muscle weakness that starts in the proximal muscles—those muscles closest to the trunk of the body. Inflammation damages the muscle fibers, causing weakness, and may affect the arteries and blood vessels that run through the muscle, including the heart. Other symptoms include fatigue after walking or standing, tripping or falling, and difficulty swallowing or breathing. Some patients may have slight muscle pain or muscles that are tender to touch. Manifestations include such things as:

-

1.•Trouble rising from a chair

-

2.•Difficulty climbing stairs or lifting arms

-

3.•Tired feeling after standing or walking

-

4.•Trouble with swallowing or breathing (dysphasia)

-

5.•Muscle pain and soreness, sometimes sever, that does not resolve after a few weeks (Fibromyalgia)

-

6.•Migraine headaches and nausea

-

7.•Known elevations in specific muscle enzymes by blood tests (CPK or aldolase)

Forms of Myositis:

Brief descriptions of each of the forms of myositis are provided below:

Polymyositis affects skeletal muscles (involved with making movement) on both sides of the body. It is rarely seen in persons under age 18; most cases are in patients between the ages of 31 and 60. In addition to symptoms listed above, progressive muscle weakness leads to difficulty swallowing, speaking, rising from a sitting position, climbing stairs, lifting objects, or reaching overhead. Patients with polymyositis may also experience arthritis, shortness of breath, and heart arrhythmias.

Dermatomyositis is characterized by a skin rash that precedes or accompanies progressive muscle weakness. The rash looks patchy, with bluish-purple or red discolorations, and characteristically develops on the eyelids and on muscles used to extend or straighten joints, including knuckles, elbows, heels, and toes. Red rashes may also occur on the face, neck, shoulders, upper chest, back, and other locations, and there may be swelling in the affected areas. The rash sometimes occurs without obvious muscle involvement. Adults with dermatomyositis may experience weight loss or a low-grade fever, have inflamed lungs, and be sensitive to light. Adult dermatomyositis, unlike polymyositis, may accompany tumors of the breast, lung, female genitalia, or bowel. Children and adults with dermatomyositis may develop calcium deposits, which appear as hard bumps under the skin or in the muscle (called calcinosis). Calcinosis, an imbalance, and sometimes severe and dangerous buildup of calcium deposits in the tissue, most often occurs 1-3 years after disease onset but may occur many years later. These deposits are seen more often in childhood dermatomyositis than in dermatomyositis that begins in adults. Dermatomyositis may be associated with collagen-vascular or autoimmune diseases.

In some cases of polymyositis and dermatomyositis, distal muscles (away from the trunk of the body, such as those in the forearms and around the ankles and wrists) may be affected as the disease progresses. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis may be associated with collagen-vascular or autoimmune diseases. Polymyositis may also be associated with infectious disorders.

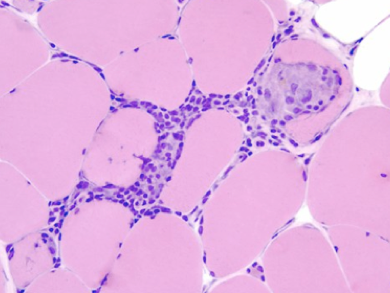

Inclusion body myositis (IBM) is characterized by progressive muscle weakness and wasting. IBM is similar to polymyositis but has its own distinctive features. The onset of muscle weakness is generally gradual (over months or years) and affects both proximal and distal muscles. Muscle weakness may affect only one side of the body. Small holes called vacuoles are seen in the cells of affected muscle fibers. Falling and tripping are usually the first noticeable symptoms of IBM. For some patients the disorder begins with weakness in the wrists and fingers that causes difficulty with pinching, buttoning, and gripping objects. There may be weakness of the wrist and finger muscles and atrophy (thinning or loss of muscle bulk) of the forearm muscles and quadricep muscles in the legs. Difficulty swallowing occurs in approximately half of IBM cases. Symptoms of the disease usually begin after the age of 50, although the disease can occur earlier. Unlike polymyositis and dermatomyositis, IBM occurs more frequently in men than in women.

Juvenile Myositis has some similarities to adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis. It typically affects children ages 2 to 15 years, with symptoms that include proximal muscle weakness and inflammation, edema (an abnormal collection of fluids within body tissues that causes swelling), muscle pain, fatigue, skin rashes, abdominal pain, fever, and contractures (chronic shortening of muscles or tendons around joints, caused by inflammation in the muscle tendons, which prevents the joints from moving freely). Children with juvenile myositis may also have difficulty swallowing and breathing, and the heart may be affected. Approximately 20 to 30 percent of children with juvenile dermatomyositis develop calcinosis. Juvenile patients may not show higher than normal levels of the muscle enzyme creatine kinase in their blood but have higher than normal levels of other muscle enzymes.

Needless to say, when reviewing the background and demographics of each from of myositis it becomes increasingly disturbing that there is extensive overlap in symptoms and reach that this disease, in its many forms, has.

Causes of Myositis (Epidemiology):

Polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and juvenile myositis are all suspected autoimmune diseases, meaning the body’s immune system is attacking the muscle. While the immune system may also cause muscle damage in inclusion body myositis, this may not be cause of this disease. Although myositis is often treatable, these diseases are poorly understood and do not always completely respond to current medications.

Inflammatory myopathies are often not diagnosed correctly. In part, this is because patients with autoimmune myopathies have many of the same symptoms as those with myositis, toxic myopathy, or muscular dystrophies, which are inherited forms of muscle disease. As a result, patients with the above symptoms should be tested and evaluated by physicians and medical staff who specialize in diseases of the muscle. However, the prevalence of the disease is so low, it is rarely seen, if ever, by most general practitioners.

As for toxic myositis, once removed from the medications causing the ailment, the symptoms often, but not always, diminish.

Disease Prevalence:

Estimates of myositis incidence range from 0.5 to 8.4 cases per million; that’s range between 1.5MM and 25.6MM individuals in the U.S. alone. The age at onset peaks between ages 10 and 15 years in childhood disease and between ages 45 and 60 years in adults. Inclusion body myositis is more common after age 50. In general, women are affected twice as often as men; however, inclusion body myositis affects twice as many men. In adults, lowest rates are reported in the Japanese and the highest in African Americans.

Population studies from the Netherlands and Sweden suggest a population prevalence of 2.2-4.9 per million, with age-adjusted rates of 16 per million in the over 50s. Polymyositis is a relatively rare disease. Women are more likely to have it than men. Although people of any age can get it, it most commonly affects people between the ages of 20 and 60 years. Children have been known to develop dermatomyositis.

Inclusion Body Myositis is listed as a “rare disease” by the Office of Rare Diseases (ORD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This means that Inclusion Body Myositis, or a subtype of Inclusion Body Myositis, affects less than 200,000 people in the US population.

Due to the rarity of this disease, and the co-morbidity of existence with other disease states and disorders, myositis is often overlooked and goes undiagnosed. It is a disease that general practitioners will rarely, if ever, be exposed to in their practice.

Diagnosis & Treatment:

Co-existence of other diseases with myositis disease is quite common such as diabetes, autoimmune diseases, peripheral neuropathy and fibromyalgia. In the case of dermatomyosits, 30% of the cases have a documented association with an underlying cancer of either breast or lung.

The chronic inflammatory myopathies cannot be cured in most adult patients but many of the symptoms can be treated. Options include medication, physical therapy, exercise, heat therapy (including microwave and ultrasound), orthotics and assistive devices, and rest. Inflammatory myopathies that are caused by medicines, a virus or other infectious agent, or exposure to a toxic substance usually abate when the harmful substance is removed or the infection is treated. If left untreated, inflammatory myopathy can cause permanent disability.

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis are first treated with high doses of prednisone or another corticosteroid drug. This is most often given as an oral medication but can be delivered intravenously. Immunosuppressant drugs, such as azathioprine and methotrexate, may reduce inflammation in patients who do not respond well to prednisone. Periodic treatment using intravenous immunoglobulin can further recovery in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis, but is ineffective for inclusion body myositis patients.

Other immunosuppressive agents that may treat the inflammation associated with dermatomyositis and polymyositis include cyclosporine A, cyclophosphamide, and tacrolimus. Physical therapy is usually recommended to prevent muscle atrophy and to regain muscle strength and range of motion. Bed rest for an extended period of time should be avoided, as patients may develop muscle atrophy, decreased muscle function, and joint contractures. A low-sodium diet may help to counter edema and cardiovascular complications.

Many patients with dermatomyositis may need a topical ointment (such as topical corticosteroids or tacrolimus) or additional treatment for their skin disorder. A high-protection sunscreen and protective clothing should be worn by all patients, particularly those who are sensitive to light. Surgery may be required to remove calcium deposits that cause nerve pain and recurrent infections.

There is no standard course of treatment for IBM. IBM is generally resistant to all therapies and its rate of progression appears to be unaffected by currently available treatments. The disease is generally unresponsive to corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs. Some evidence suggests that intravenous immunoglobulin may have a slight, but short-lasting, beneficial effect in a small number of cases. Physical therapy may be helpful in maintaining mobility. Other therapy is symptomatic and supportive.

Most cases of dermatomyositis respond to therapy. The disease is usually more severe and resistant to therapy in individuals with cardiac or pulmonary problems.

The prognosis for polymyositis varies. Most patients respond fairly well to therapy, but some patients have a more severe disease that does not respond adequately to therapies and are left with significant disability. In rare cases patients with severe and progressive muscle weakness can have respiratory failure or pneumonia. Difficulty swallowing can lead to becoming malnourished.

Research:

Research into myositis is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and other institutes of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct research relating to dermatomyositis in laboratories at the NIH and support additional research through grants to major medical institutions across the country. Currently funded research is exploring patterns of gene expression among the inflammatory myopathies, the role of viral infection as a precursor to the disorders, and the safety and efficacy of various treatment regimens.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH), through the collaborative efforts of its National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), conducts and supports a wide range of research on neuromuscular disorders, including myositis and the inflammatory myopathies.

Scientists are conducting studies to determine the safety and effectiveness of alemtuzumab in improving muscle strength in patients with IBM. This laboratory-made antibody has been used to treat patients with autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, vasculitis, multiple sclerosis, and tissue rejection associated with transplantation.

Additionally, since IBM appears to have a different epidemiology, researchers are also studying IBM patients to learn how muscle inflammation destroys muscle fiber and causes weakness. Study results may lead to a new treatment for the disease. The muscle fiber physiology of IBM is remarkably similar to protein accumulation damage seen in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Both hereditary IBM and AD muscle fibers are injured by oxidative stress — the buildup of certain molecules that contributes to autoimmune diseases and inflammation. NIH-funded research is examining the mechanisms and molecular changes involved in the early buildup of harmful proteins that leads to vacuolar (involving holes in cells) muscle fiber degeneration.

Scientists are developing mouse models to study beta-amyloid peptide buildup and its role in IBM and age-related muscle disease. This harmful accumulation in IBM occurs outside the central nervous system and is not present in other muscle disorders. Another study is investigating the beta-amyloid buildup and its role in inducing apoptosis, or cell death.

The NINDS and NIAMS are funding DNA analyses using microarrays to characterize patterns of muscle gene expression among adult and juvenile patients with distinct subtypes of inflammatory myopathies. Findings will be used to refine disease classification and provide clues to the pathology of these disorders.

Other NIH-funded research is studying prior viral infection as a precursor to inflammatory myopathy. Scientists are using a mouse model of chronic inflammatory myopathy to identify specific viral genes that are crucial to disease development.

NIH-funded researchers are also studying childhood-onset polymyositis and dermatomyositis to learn more about their causes, immune system changes throughout the course of the disease, and associated medical problems. Scientists are studying inflammation and how skeletal muscle degeneration leads to weakness and muscle wasting. NIEHS researchers are also studying immunogenetic and environmental risk factors for these diseases. Other research hopes to determine whether the drug infliximab, which blocks a protein that is associated with harmful inflammation, is safe and effective in treating dermatomyositis and polymyositis.

NIH-funded researchers are also studying the effectiveness and safety of the antitumor necrosis factor drug etanercept in new-onset dermatomyositis and the safety and effectiveness of rituximab, a monoclonal antibody directed against B cells, in reducing inflammation in patients with dermatomyositis, polymyositis, or juvenile dermatomyositis.

Conclusion:

The reality is simply this; according to the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, Arthritis Foundations and others; publications and research on myositis are on the decline It’s imperative that this “rare disease” disorder gets the funding and attention required for the millions of individuals (and their families) who affected and impacted by this insidious and progressive disease.

a little About myositis: